COVID-19: Science and Public Policy

By Maheen Attique

Source: https://www.azuravesta.com/covid-19-pandemic

Did we ever imagine that we would live to see the day the world would come to a stop at the expense of something as microscopic as a viral pathogen? The short answer is no, we did not. The correct answer is we should have.

Learners’ Republic and Genes & Machines, organized a dialogue between economists/policy practitioners and scientists/health professionals on April 15, 2020. Hassnain Qasim Bokhari and Dr. Naveed Iftikhar moderated the dialogue. The idea was to especially focus on the science of COVID 19 and to suggest appropriate and effective policy responses.

What is COVID-19 and how is it detected?

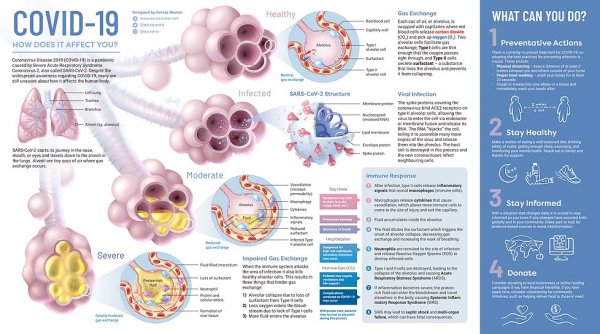

A report published by the World Health Organization in February 2020 about Sars-CoV-2, or Coronavirus as it is commonly known, explains that it has zoonotic origins and appears to have originated from bats1. Although there is no confirmation on an intermediate host, it is widely believed to have passed through pangolins – scaly anteaters of the mammal classification – to humans2. According to Dr. Nasir Jalal, a Health and Biotech Partner at CDI Global, the virus is a mutated version of the SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV-1) and is multi-variant in nature. It is encapsulated by an outer surface protein with crown-like spikes on it, which are unstable. This makes it harder to develop a single vaccine to treat multiple strains of the same virus. Once the virus infects human cells, it replicates itself and spreads to the respiratory system. The virus is estimated to have an incubation period of 7 days3, during which asymptomatic conditions may develop. After this, the infected person usually starts showing symptoms such as dry cough, fever and body shivers. At this point, there is an increase in the immunoglobulin compounds IgG and IgM in the blood – which are antibodies – as your immune system tries to fight off the virus. Thus, a person who tests positive for the presence of these agents in their blood may be either actively infected or recovered4.

To diagnose the infection, there are two methods that are currently available. The first one is the Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) test which uses a sample – a nose or throat swab – to detect whether the person is positive for Coronavirus. This requires test tubes carrying the person’s extracted RNA to be placed in an RT-PCR machine and exposed to fluorescent probes to reveal results5. According to Dr. Jalal, this method, despite being the most reliable, is expensive, time intensive (takes 2-3 days) and necessitates skilled professionals to perform the test in well-equipped diagnostic labs. The second approach uses rapid testing kits that measure the presence of the IgG and IgM molecules in blood plasma to detect whether the person has COVID-19. As the name suggests, the test is rapid (takes 10-15 minutes), relatively inexpensive and can be performed at home even6.

What is the situation in Pakistan?

With 144 recorded deaths as of 18th April 2020, the current death rate stands at 1.9%7, which is fairly lower than some of the most-affected European countries. However, while comparative statistics might oblige one to believe the country is doing relatively better on the global scale, it must be noted that these figures might be misleading. Dr. Fyezah Jehan, an epidemiologist at Aga Khan University, cites the lack of appropriate testing as the main reason why we cannot rely on these numbers alone. “On April 14, for instance, Punjab carried out 2000 tests whereas the rest of the provinces barely conducted a thousand. This indicates why we have a higher number of cases in Punjab – not because the other provinces are doing better but because they are just not testing enough”, she explains. She goes on to add how 30-35% of the population displays asymptomatic conditions which renders them being excluded from the tally of active cases.

Testing is a predominant issue worldwide, but for developing countries like Pakistan, it is even more profound. Even with the few diagnostic labs we have, the PCR machines require certain ingredients to operate which are imported from other countries. With trade flows hampered, this has become difficult. While rapid testing kits are gaining traction abroad, Pakistan remains one of the countries that still do not have wide-ranging access to them.

What does this say about our existing policy frameworks?

“It is a massive expose”, says Dr. Faisal Khan, a PhD in Systems Biology from Oxford University, currently the PI at Precision Medicine Lab, Pakistan.

The pandemic has lifted the veil on how prepared our government is to deal with crises of this nature. It is a startling revelation on how low science and innovation are ranked on the order of priority, leading to severely underdeveloped critical mass of infrastructure and an incapable response from officials. The country has no effective legislation regarding epidemics. As a result, we have officials from the NDMA at the frontline of the country’s fight against Coronavirus, instead of health professionals. It was discussed that the efficiency and relevance of spending on scientific research does need improvement.

What needs to be done?

1. Ensuring reliable dissemination of accurate information to the public regarding safety protocols and procedures

- This is especially important in the case of indigenous Health Care Workers who might not have access to this information easily

2. Increasing capacity through pooling resources

- Conduct regular dialogues between professionals from various disciplines to ensure policy interventions are multi-faceted in nature

- Organize science and policy experts from around the country in strategic planning and management to formulate holistic and effective interventions

- Outsource research equipment and laboratories from country’s leading universities and institutes to researchers

- Give agency to any and all individuals willing to conduct research, rather than encouraging a selective few

3. Allocating special funds and grants for good quality research and innovation

- Advance QA/QC checks to ensure research expenditure is worthwhile

- Encourage public-private collaboration so that the private sector can engage in research under the government’s patronage

4. Fast tracking regulatory procedures to reduce red-tapism

- This is especially important in facilitating drug approvals through the Drug Regulation Authority Pakistan

5. Training students and faculty through capacity-building programs

- Improve learning outcomes of the students by developing their critical thinking abilities to enhance their problem-solving skills

- Encourage business skills and entrepreneurial mindsets to design solutions and earn returns on them

6. Collecting disaggregated data across different variables, especially gender and among marginalized communities, to build better predictive models and policy frameworks for preparing for similar crises in the future

Looking forward

When will this pandemic end? This is an uncertain question. But something that is absolutely certain is that there will be more to follow. With climate change, stoppage of vaccination campaigns as a result of lockdowns, over-burdening of the healthcare infrastructure, we might encounter similar situations more frequently in the future. There is a need for governments and policymakers around the world to promote research on biotechnology and health sciences.

Do we want to be caught unawares next time? The correct answer is no, we do not. The best thing to do, then, is to prepare ourselves, and plan better.

—————

Maheen Attique is a student of Economics and Mathematics at the Lahore University of Management Sciences. She harbours a passion for public policy and community engagement and hopes to one day follow up on it through impactful work.

3 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7014672/

4https://blogs.sciencemag.org/pipeline/archives/2020/04/02/antibody-tests-for-the-coronavirus

5 https://www.businessinsider.com/how-coronavirus-throat-tests-work-rt-pcr-method-explained-2020-4

6 https://www.elabscience.com/p-covid_19_igg_igm_rapid_test-375335.html