Anti-Encroachment-Drive

By Fizza Amjad

Since April 2015 (Dawn, 2015), successive governments in Pakistan have adopted an “Anti-Encroachment” policy at the national level. The latest iteration was a Presidential Ordinance promulgated under Article 89 of the Constitution in August 2021 (The Express Tribune, 2021). Essentially, the national policy is designed to provide a legal framework to act against illegal encroachment of public land. The policy explicitly sanctions seizures and the use of force (Business Recorder, 2021), in addition to fines and imprisonment (The Express Tribune, 2021).

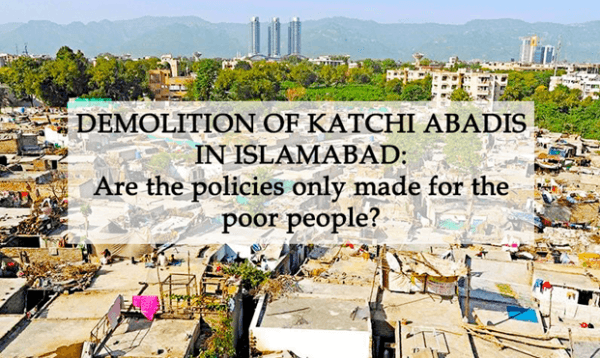

The Capital Development Authority (CDA) in the country’s capital, Islamabad, has used the national anti-encroachment policy as the basis for its aggressive plans to recover land from illegal occupation across the city. In the CDA’s own words, they have used the might of the Capital Police to have “an action plan aimed at the implementation” (Albrechts and Balducci, 2013, pg.17), forcibly evict residents and demolish structures across the city to reclaim land owned by the CDA (CDA Website, 2018). The brunt of this policy has been borne by the residents of katchi abadis (informal settlements housed by labourers and migrants employed in low-wage jobs) and khokas (informal food stalls set up for serving food to the blue-collar workers). For instance, CDA has razed hundreds of khokhas (Zulfikar, 2020, pg.6) without warning and demolished entire settlement communities (Pro Pakistani, 2021). These jobless and homeless are primarily domestic and sanitation workers priced out of other housing options in the city.

The CDA’s drive relies heavily on the national anti-encroachment policy. Firstly, the national policy itself refers to the master plan for Islamabad published in 1960 (Doxiadus, 1960), which introduced spatial zoning without any unplanned areas. It effectively deems illegal all “unplanned” and ad-hoc solutions for low-cost housing for low-wage workers. Secondly, the national policy sanctions using force to evict residents and demolish structures. It has enabled the CDA to utilize excessive force to achieve its objectives. Finally, the national policy fails to specify appropriate repatriation and compensation for the affectees, allowing the CDA to act without worrying about consequences and associated costs.

CDA’s anti-encroachment drive has centred squarely on the khokhas and katchi abadis, despite several other instances of encroachment on CDA-owned land. For example, the country’s Prime Minister’s residence in Bani Gala has been deemed an encroachment. Still, the CDA moved quickly to regularize it- a fate starkly different compared to the residents of the katchi abadis (Dawn, 2020). The CDA’s drive has led to widespread condemnation. In a city that needs its low-wage workforce desperately, the CDA is clearing them out without any alternatives and no compensation (The Express Tribune, 2020). As one would expect from such an aggressive action plan, vested interests within the CDA have abused their authority and destroyed several legitimate businesses to further personal interests (The News, 2018).

The above factors point to the aggressive and interest-based implementation of the policy and plan as opposed to what Elcock, 2006, states about the government defending citizens’ fundamental rights and engaging in commerce. Instead, the most vulnerable segments of society are suffering.

Retrospect: Whose interests are represented in ‘Anti-Encroachment Drive’?

In theory, the Anti-Encroachment national policy in Pakistan and its implementation by the Capital Development Authority (CDA) in Islamabad are motivated by general public interest. Specifically, the national policy aims to regain control of Government lands encroached upon illegally. In theory, this should benefit the tax-payer and general public because the lands can be put to their best economic, environmental, societal and developmental use (Elock, 2006). However, such objectives can only be met if all competing interests are represented in the policy- and implementation- planning stages. Whether the policy was correct or preferable can be assessed from the consequences after implementing it. (Wheeler, 2006, pg.23)

The interests of influential political and economic groups have been well-represented in the national parliament and cabinet, influencing the policy. Additionally, they are well-represented in the CDA, directly affecting the implementation plans. For example, a vast housing society built on 6000 kanals encroached on government land (forest area), called the Bahria Town, has consistently gotten away with paying small fines to regularize their encroachment instead of handing over control back to the government (Dawn, 2019). Further, the Prime Minister’s sprawling residence in Bani Gala, built on entirely encroached land, was hastily regularized without any penalties (Dawn, 2020). In a familiar and expected pattern, none of the major shopping malls, housing complexes, or office complexes for the wealthy but built on encroached land have faced the wrath of the CDA, similar to the demolition jobs suffered by the katchi abadis and khokas.

Unfortunately, catering to the wealthy and influential’s economic, personal and political interests cannot count as acting in the public interest. The definition of public interest by Wheeler, 2006, states that “..considerations affecting the good order and functioning of the community and government affairs for the well-being of citizens” (pg.14). The anti-encroachment national policy does not take into account the well-being of the most impacted citizens. None of these citizens is represented in the federal or local governing bodies, and the only political parties representing them (e.g. the Awami Workers Party) have remained unelected (ECP, 2018). Thousands of people have been rendered homeless (The News, 2018; Pro Pakistani, 2021), with no compensation or alternatives provided to the affectees. In just one such demolition drive in Islamabad, it is estimated that 25,000 of the poorest citizens were directly or indirectly impacted (Bashir, 2020, pg.14). The economic, political and societal costs of these operations have been ignored by the people and the impact on their lives and livelihoods. The impacted people are mostly low-wage workers keeping the major urban centres functional who are now left with no housing and sanitation options. It is impossible to conclude that the anti-encroachment policy and its implementations acted in the public interest.