The Right to the City in Karachi

By Mahnoor Khan & Asiya Syed

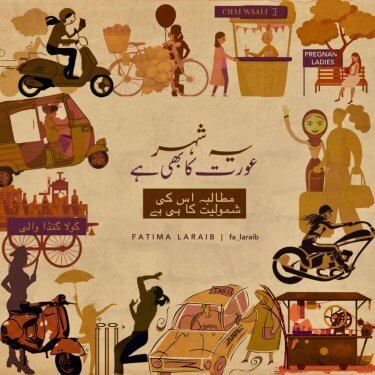

Visual art by Fatima Laraib, illustrating the right to the city actualised by Pakistani women

Having grown accustomed to the pervasive class and gender-based inequalities, often reflected in the design of our cities, we have also begun to understand our cities as neutral entities, as structures made from brick and concrete. This illusion of cities being independent from its people is at the root of several urban challenges we see today.

In Pakistan, cities are not democratically accessible to their residents, only servicing a select few who groups of people – the economically well to do. There are clear disparities to be seen within Karachi, the largest metropolitan hub in the country. Among the many issues that plague the city, the most pressing one is the increasing cost of living, leading to marked disparity, especially among young people who can now be placed in the dichotomy of the ‘haves’ and ‘have-nots.’ Those with generational wealth can afford to live and thrive in the city, renting apartments and houses at exorbitant rates, while young people from middle class backgrounds scramble to keep up with the ludicrously expensive real estate.

The state has evidently failed with regards to providing affordable and safe housing to its citizens, and those, from the civil society, who attempted to do the job had to pay heavily for it. Parveen Rehman, the prominent social activist who spearheaded the Orangi Pilot Project, was assassinated in 2013, most likely on account of her efforts to provide dignified housing to those living in poverty. The disparity she sought to counteract has only grown worse in recent years, with the forced evictions of street vendors in Saddar, who had occupied the same area for years, if not decades prior. This attempt to ‘sanitize’ the city by hiding its poor populace caters to the ideals of modern aestheticism. Sleek roads and buildings are not the way forward. We need to invest in healthcare, education and other fundamental rights to be made accessible to the entire population. Our present fixation with megaprojects and megacities thoroughly detracts from the ever-pressing concern that is the degrading quality of life for city residents.

New housing projects for the elite, or the beautification of round-abouts, do very little to address the central concerns that residents are being faced with on a day to day basis. We must channel resources where they are needed the most: not in superficial attempts to make cities look “cleaner” or the aesthetically-guided revivals of dilapidated buildings. Need of the moment is to provide citizens with their fundamental rights which, according to David Harvey, are possessed by every individual who makes a contribution in society regardless of their class, caste, gender or religion. It is ironic, that while Karachi runs on the labor of working-class women, immigrants and the youth, none of them are accounted for in the structure of the city. Anyone who has visited Karachi can attest that the city’s transport system and infrastructure caters predominantly to the affluent car owners: roads are widened every few years to accommodate the growing number of private vehicles, yet no attempts are made to improve public transport even though it facilitates most frontline or daily wage workers. Karachi’s abysmal infrastructure came to light during the monsoon rains of 2020, which devastated the entire city, particularly those areas that housed the working class. Yet, most attention was given to the Defence Housing Authority (DHA). Improperly built sewage and drainage systems led to flooding in arguably the wealthiest part of the city and therefore were majorly covered by the media. This not only exposed massive infrastructure flaws, but also the elitist nature of the city, which defies the very notion of a democratic ownership.

Now, with the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, our lack of investment in infrastructure, housing and healthcare has become embarrassingly clear. Overcrowding in slums and informal settlements has meant that the virus can spread like wildfire because these are areas that the state deemed unworthy of investment. Even before the onset of COVID-19, the poor were disproportionately affected by elitist policies and urban planning. There are no walkways that can cater to pedestrians, no hospitals in the vicinity of low-income areas, no infrastructure to deal with monsoon rains or even routine rainfall. It is disgraceful for us, as citizens, to confront the treatment of our urban-poor, whose collective efforts are the reason this city- and all cities- stay afloat.

The city, like the country, is home to everyone who inhabits it. If we were to map David Harvey’s understanding of what it means for residents to stake their claim in their cities onto Pakistan, we would realize how far we are from achieving such cities. A city to which everyone has an equal right is nearly inconceivable for the reasons stated above, and due to the fact that we cater only to those we deem worthy: not women, not the young, not the elderly, and certainly not the differently abled.

This does not have to be our reality. According to Jane Jacobs, in saving our city, we have the power to save ourselves. The pandemic has made it abundantly clear that access to healthcare, food, sanitation, transport and housing is a human right, not a right one must “earn”. Existence in itself entitles one to a life of dignity. This is the standard we must adopt if we wish to save our cities andby extension- ourselves.

——————————–

Mahnoor Khan is pursuing a history major at LUMS and holds an interest in urban planning.

Asiya Syed is an anthropology/sociology student at LUMS with a keen interest in the histories of people and places.